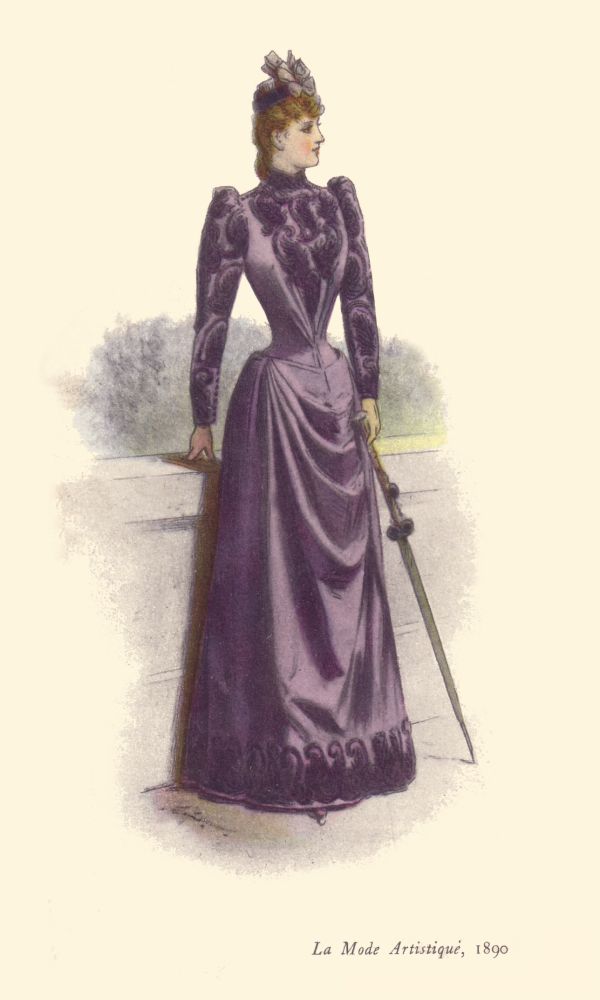

The Mauve Decade

by Judith Hollenberger Dunlap. Originally published for the November/December 2012 issue of Finery.

Mauve was the first color of aniline dye discovered by William Henry Perkins as he searched for an artificial way to make quinine. The aniline dyes he developed in the latter half of the 19th century opened up fashion to an array of new colors, but mauve was so popular that the 1890s was nicknamed ‘The Mauve Decade’ by Thomas Beer in 1926 when he wrote his treatise on 1890s American manners.

In general, during the final decade of the 19th century women’s daywear consisted of a tight-fitting bodice over a skirt gathered at the waist and falling over the hips to the ground. Women continued to wear corsets under their bodices and petticoats under their dresses, but they also wore a wider variety of less restrictive clothing such as tea gowns, tennis dresses, and bicycling costumes. Tailor-mades, native to England and adopted by women in America, were a masculine style similar to English riding habits. They emerged in England in the late 1870s, migrated to America and continued to be popular, reflecting the growing movements for women’s emancipation in America and England

Bicycling exploded in popularity with the introduction of the safety bicycle. The safety bicycle had two wheels of equal size and a chain drive that transferred power to the rear wheel. Earlier bicycles had large front wheels driven by the pedals, so riding took great strength and the early ‘high wheelers’ were difficult for women to handle, especially in their restrictive clothing. In America women’s efforts for suffrage were intertwined with their passion for bicycling. In fact, in 1896 Susan B. Anthony told the New York World’s Nellie Bly that bicycling had “done more to emancipate woman than anything else in the world.” Nellie Bly (the pen name of journalist Elizabeth Jane Cochrane) had just six years earlier set a world record and beaten the fictitious Phileas Fogg’s feat of traveling around the world in 80 days by completing her journey in just under 73 days.

England celebrated a revival of trade in the 1890s as well as the Diamond Jubilee. The quality of clothing, however, declined and cheap substitutes were added such as inferior linings and lace. The blouse and skirt became the hallmark of the middle and upper class woman. The beginning of the decade heralded simplicity in daywear in England and America. Paris, however, continued to prefer oodles of trimmings. Open Princess robes over underskirts provided a more dressy option for American and English women when needed. The S-bend corset arose, as did the trumpet skirt. Both would survive into the Belle Époque and beyond.

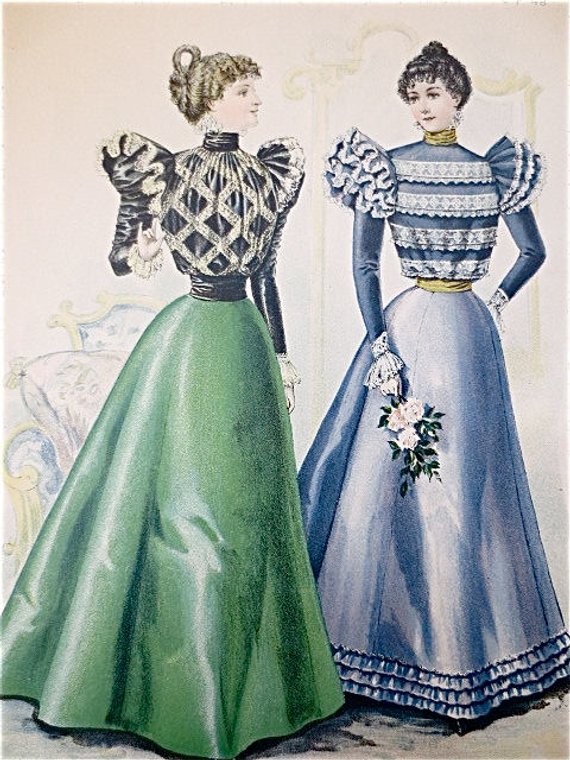

Early 1890s bodices were full in front and fussily draped and frilled, in contrast to the plain skirts. Shoulder lines broadened in 1892, bolstered by huge upper sleeves and pelerine lapels. These elements were designed to suggest a small waist. International events added a Russian influence to some fashions. There was a lengthening and enlargement of the skirt. Skirts were gored to increase their bottom circumference. Bodices featured yokes and lots of frills along with the large sleeves so iconic of the early 90s.

By 1893 we saw a “fashion remarkable for its exaggerations.” Gored skirts expanded and were lined with crinoline nearly up to the knees. Bodices featured bright contrasting colors. The French reintroduced an overskirt but American and English women retained their single skirts, although they increased in size. Customers clamored for ready-made blouses. Skirts were bell shaped and topped with yoked blouses dripping with lace and Eton jackets with gigot sleeves. It came to a point where a “well-dressed woman can scarcely enter straight through a doorway.”

1895 saw the apex of the ballooning sleeves. Colors were vivid and collars enlarged. Women struggled to find bicycling costumes that would allow them to ride but preserve their modesty. French women wore huge Zouave knickerbockers, English women tended towards solutions with skirts. In all cases they found covering their legs difficult. Sleeves could no longer support themselves and collapsed in 1896. They retreated to the shoulder, leaving a puff or frill at the shoulder with a close fitting sleeve to the wrist. Even day skirts lost some of their volume and shortened, as much as three to four inches off the ground. Trimming remained and became even more feminine. Petticoats featured multiple flounces. Bodices remained loose in the front but the overall silhouette was an hourglass. Softer fabrics came into vogue, with lots of lace. Fashion emphasized the height of a lady.

1897 saw even bigger changes. Dresses became fluffy and frilly, they rippled and rustled. Colors went from bright to harmonious. Trimmings were light and flimsy. Clothing outlines were soft, meant to give a willowy, slender impression. One theory is that the increased softness and femininity of clothing was a reaction to the widening movement for women’s emancipation and her adoption of cycling, tennis, and other sports. Threats of increased independence were gentled by softer fashions. England also had increased prosperity, allowing more luxury in clothes. This year was the apex of the petticoat. One writer described women as “plunged up to the knees in an enormous meringue.”

1898 saw a lengthening of dresses; even tailor-mades touched the ground. Dresses were clinging and soft, emphasizing the hips and height. Colors were monochrome and the Princess line came back strongly. By 1899 English and American women’s fashions reflected individualism and athleticism, but were still restrictive. Skirts such as the ‘eel skirt’, cut on the cross, tight fitting from the waist, close fitting over the hips and down to the knees, then flaring out below, turned walking into a sort of gliding motion. A lady’s upper half was swathed in material, with overskirts and Princess dresses increasing. Skirt pleats were commonly stitched down to the knee.

The 1890s witnessed the birth of ‘the Gibson Girl’, illustrations penned by Charles Dana Gibson delineating an American ideal of feminine beauty. She was independent and athletic, but also soft and feminine. The ideal of the Gibson Girl carried on well into the twentieth century. The 1890s also saw the rise of dress reform efforts from both the Aesthetic artistic movement and a widespread health movement fired by women’s newfound participation in sports and appreciation for clothing that allowed them more freedom of movement. Did clothes drive the expansion of women’s intellectual, financial, and emotional freedom or did their expansion force fashion accommodations? We can absolutely say that the decade of the 1890s saw drastic evolution of our contours, both internal and external.

Leave a comment